Those gifted to sell can sell even what they know little about. Experts can sell only if pressed for details of little concern to customers.

That said, shooters and hunters pay increasing attention to details. And they know more than their forebears. They buy most readily from people who can answer their questions.

Lead-free bullets have multiplied in a market with myriad bullet options. Depending on who tells the story, they’re a burden from environmentalists or a boon to hunters. Both claims apply. However you view lead-free bullets, they’re properly called just that: lead-free. To say they’re non-toxic implies that lead-core bullets pose an environmental hazard. Science hasn’t confirmed this.

Claims of a spent-bullet threat have little in common with the evidence nixing use of lead shot for waterfowl. Ducks daily ingest grit in the shallows fronting blinds from which hunters may fire hundreds of rounds annually. Each cloud of pellets sent aloft falls on spent shot already carpeting the bottom, where waterfowl forage. But while some marshes rock with volleys of gunfire daily, big-game hunters disperse widely, each likely to return with a clean barrel. Bullets that kill often pass through, landing harmlessly, as do those that miss. Bullet shards lodging in the beast typically leave the field with the carcass. Those in offal may or may not be available to scavengers. No birds or mammals that routinely eat carrion need grit.

Is lead toxic? Certainly. So is copper — in bullets, pennies, wiring and kitchenware.

Shooters with an eye to ballistics might ask how lead-free bullets stack up against jacketed.

Actually, lead-free came first. The first firearms used rocks and scrap iron as projectiles. By the time rifling appeared in the 16th century, hunters were using lead balls. Conical bullets with hollow skirts that bulged to snug the bore gained fame during our Civil War, courtesy of Captain Claude Minie (meeNAY). Buffalo hunters favored long bullets that had enough inertia to boost reach and penetration. Adding 10 percent tin to the lead increased hardness and reduced fouling as velocities climbed (pure lead melted into rifling at speeds over l,200 fps). An alloy with 5 percent tin, 5 percent antimony bumped the ceiling to 1,500 fps. Bullet jackets would follow.

Our .30-40 Krag, with the .30 WCF and its lever-rifle kin, used jacketed softnose bullets in the 1890s, but they weren’t pointed. In 1905, Germany replaced its round-nose 226-grain 7.9x57 bullet at 2,090 fps with a 154-grain spitzer at 2,880. Bullet diameter changed from .318 to .323 (8mm). Letter suffixes distinguished these two “8mm Mausers”: J for .318, S for .323. Inspired, the U.S. updated the .30-03 with a pointed 150-grain bullet at 2,700 fps to produce the .30-06. Such high speeds prompted new jackets. After tin plating was found to “cold-solder” to case mouths, Western Cartridge fielded an alloy incorporating tin. This “Lubaloy” jacket protected bullet cores above Mach 3.

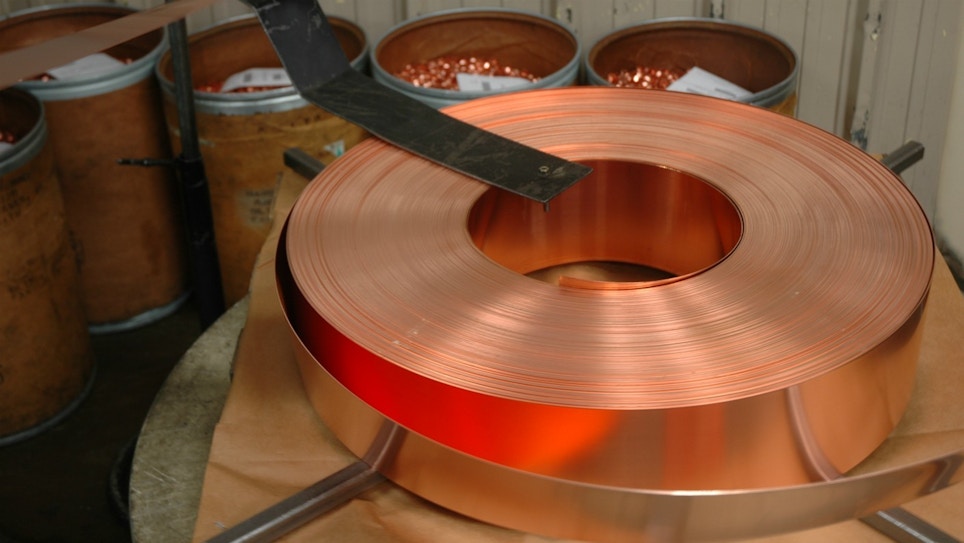

Fast-forward a century. Lead bullet cores haven’t changed much. Most now contain a measured dose of antimony to make them harder (2.5 percent is common, 6 percent about the limit). Cores are lopped from lead wire or extruded from bar stock, then annealed. Forming dies marry cores with jacket cups. Most jackets are of gilding metal, 95-5 copper-zinc. Ductile copper jackets yield beautiful mushrooms in game, but copper residue also adheres to rifling.

Randy Brooks told me he was hunting brown bears when it occurred to him that bullet failures in tough animals all involved lead loss. So back at his Utah shop, he developed an all-copper hollowpoint. “I called it the X-Bullet because the nose peeled into four petals: an X,” he said. In 1989, Randy and wife Coni bet their Barnes Bullets business on that design and set about proving it afield. He emphasized the X-Bullet came from his search for a better bullet, not a lead-free one. The toxicity issue wasn’t yet news.

Then in July 2008, a ban on lead bullets in parts of California followed a lawsuit from the Center for Biological Diversity and similar groups. The litigants claimed that failure to ban lead bullets put the State at odds with the Endangered Species Act. California’s Fish and Game Commission caved.

In bullets, few materials rival copper as a replacement for lead. Still, it’s not perfect. Relative to lead, copper has low specific gravity. A lead bullet has greater sectional density than a copper bullet of the same length, and given the same speed, lead hits harder. Making copper bullets longer to boost weight has its limits. Stabilizing long bullets requires faster rifling twist. Longer shanks add friction, which increases pressure. Cartridges exceed the standard length for magazines or barrel throats unless long bullets are seated deep, eating into powder capacity. Copper is harder than lead; gilding metal harder still. So lead-free bullets can’t be pushed faster than same-weight jacketed bullets without increasing pressure. On top of that, copper costs more than lead.

But success with the X-Bullet prompted Randy Brooks to refine it. Three shank grooves reduced friction and gave rifling “a place to push displaced copper.” Result: lower pressure, less fouling, better accuracy! In 2003, this bullet became the TSX or Triple Shock.

The copper TSX has since been joined by copper-alloy bullets by Hornady, Nosler, Winchester and Federal. Nosler’s E-Tip bullet was introduced by Winchester under the Combined Technology banner in 2007. Glen Weeks, then centerfire guru at Olin’s Winchester plant, noted the E-Tip’s 95/5 alloy “won’t foul bores as badly as copper.” Lubalox coating further reduced fouling. To ease barrel passage, the E-Tip’s cavity extends below the ogive, so acceleration slugs the bullet into the rifling. Like the TSX, the E-Tip was hawked as a deep-driving bullet that upset to double diameter and lost little if any weight in game. E-Tips have since left Winchester’s line, supplanted by the Super X Power Core, then in 2018 by the Deer Season Copper Impact bullet. E-Tips are still cataloged by Nosler.

Hornady’s lead-free GMX (gilding metal expanding) bullet arrived early in 2009. Jeremy Millard headed that project. “GMX bullets are a 95/5 alloy,” he said, “and cost 40 percent more than lead bullets to make.” Similar in profile and flight to Hornady’s SST, the GMX does have a different nose. “A parallel-sided cavity tapers to a point even with the base of the ogive, so expansion stops there, above two shank grooves,” Millard said. “Our accuracy and pressure tests showed no advantage to additional grooves.”

In 2011, Hornady wedded the GMX shank with the soft-poly FTX tip of LeverEvolution ammo to produce the MonoFlex. A 140-grain 30-caliber MFX scales 20 grains less than its lead-core counterpart. The nose cavity differs, too. “Lead grips soft polymer stems tightly,” an engineer told me. “Copper allows soft tips to slip. The long MFX stem bottoms in a deep cavity that helps ensure full upset.”

Federal’s Trophy Copper bullet is of copper alloy with a polymer tip. Its shank has four grooves. There’s also a Trophy Copper shotgun slug, and, new at this writing, Power-Shok Copper bullets.

The Barnes MRX bullet, like the Tipped TSX, has a sharp polymer nose and three shank grooves. It also boasts a Silvex heel core. Heavier than lead, this material hikes sectional density and penetration.

Black Hills, noted for handgun and Cowboy Action ammo as well as centerfire rifle loads, has a new HoneyBadger line that includes a 325-grain copper .45-70 bullet that’s fluted, without a nose cavity. In trials, non-deforming HoneyBadgers have yielded deeper penetration and larger wounds than hollowpoints.

Jacketed and lead-free expanding bullets rely on impact velocity to open. Most are built to upset at 1,600 fps, an easy threshold with modern loads out to 500 yards. But long-range shooting requires broader sure-upset windows. Lead has the edge here. Hornady’s Millard says, “it’s hard to make copper upset at less than 2,000 fps unless the cavity is so big it trims ballistic coefficient and the nose fragments. The slender noses of lead-free bullets smaller than 6.5mm make expansion even harder to regulate.” Still, new tip materials and nose designs promise reliable upset at lower velocity thresholds from both jacketed and lead-free bullets.

Selling Lead-Free Bullets

Here are some things you’ll need to keep in mind in order to sell more lead-free bullets or ammo

1. You have limited time. Burn a minute listening. If the customer doesn’t know an X-Bullet from an X-Box, you must start in a different place than if he quickly launches into drag coefficients. Learn about his favorite rifles and loads, his hunting style, what he expects of bullets. You’re looking for a need to fill!

2. Clarify terms: “Solid copper” doesn’t mean non-expanding. Aside from true solids made for Africa’s heaviest animals, lead-free bullets are made to expand in deer-size game; “solid” can mean unalloyed copper or gilding metal. “Controlled expansion” suggests throttled upset and deep penetration, but it applies to all expanding bullets. Each is fashioned to follow a specific protocol upon impact. Lead-free bullet upset depends on velocity and the target medium as well as bullet design.

3. Come clean on ballistic comparisons of lead bullets versus lead-free. In trajectory, accuracy and lethality, they’re essentially equals out to four-figure shot distances. You just have to choose intelligently.

4. Explain VLD (very low drag) profile. A long ogive flattens bullet arc and reduces deceleration rate. So does a tapered heel (boat-tail). But neither, while boosting ballistic coefficient, materially affects flight shy of 300 yards. Given a pointed or spitzer profile, the sharpness of a bullet’s tip has even less influence.

5. Talk sense about long shooting. Bullets designed for extreme range have lead cores. Hard poly tips of Hornady ELD and Federal Edge TRL bullets prevent shift in ballistic coefficients during extended high-speed travel — but they offer no advantage until tip temperatures exceed 700 F. Think: launch speeds of at least 3,000 fps, G1 BCs over .500, targets more than 800 yards off.

6. Dispel myths. “Some bullets go so fast they zip through game without opening.” Oh? Ask the customer to imagine a sports car that goes so fast it zips through bridge abutments without damage. The challenge for engineers: design bullets that open at low impact speeds but yield cohesive mushrooms when driven into moose shoulders above Mach 3.

7. Assure the customer that tipped bullets aren’t just hollowpoints capped. A polymer tip makes the bullet’s nose more uniform. Tip and core are designed to work together upon and after impact to initiate and throttle upset.

8. Concerning lead-core OTM (open-tip match) bullets, quote bullet-makers who discourage their use on game: “We see curved tracks in gelatin, unreliable penetration. The nose can shatter on impact or collapse to close the cavity. It can also shear, causing the heel to tumble.”

9. Note that lead-free bullets drive more reliably through bone, retain more of their original weight (often 99 percent!) and exit more often than do lead-core bullets. Modest exit wounds belie lethal damage inside.

10. Concede that while some early lead-free bullets weren’t accurate, current versions nip groups as tight as hunting rifles manage with any bullet. Cleaning might require more passes with brush and solvent, but that bore will shoot accurately as long as it would on a lead-core diet.

11. Point out that for any given bore, the heaviest lead-free bullets often beg steeper-than-standard rifling twist; however, for all but these extra-long spitzers, ordinary spin rates work fine.

12. Confirm that not all lead-free bullets are of solid stock. DRT bullets have sintered cores (compressed metal). Ditto the Nosler Ballistic Tip Varmint, Barnes MPG and Varmint Grenade, and Hornady’s NTX. These are generally for small-bore rifles.

13. Clinch a sale by dismissing price. As components or in loaded ammo, lead-free bullets are pricier than standard softpoints. So are bonded bullets. Ask the customer how much he spends filling the tank on his pickup, and then ask how many bullets he intends to fire at big game next season.